TSMC: Precision Built, Now Politically Pulled

TSMC’s brilliance was built on singular focus and neutrality. Can it thrive in a world that demands fragmentation and allegiance?

TLDR

· From Precision to Politics: TSMC’s original moat—concentrated, neutral, and ultra-efficient manufacturing in Taiwan—is being eroded by geopolitical demands that force it to fragment operations across borders, diluting both margins and strategic coherence.

· Strategic Surrender in Arizona: The $165B U.S. expansion, including cutting-edge 2nm fabs, marks a fundamental shift. What was once a business built on efficiency is now being reshaped by national security mandates, customer pressure, and redundancy politics.

· Unit-Economics Upended: TSMC’s classic model—high-yield, Taiwan-centric scale driving best-in-class margins—is being displaced by a geopolitically imposed, multi-site footprint that carries 4-5× capex, slower learning curves, and only transient “security premiums,” rewriting the very operating math that once made the foundry unbeatable.

Morris Chang was already a semiconductor veteran when he made the most contrarian bet of his career. After two decades at Texas Instruments, the 56-year-old engineer founded Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company in 1987 with a radical proposition: build a company that would manufacture chips designed by others, with no products of its own.

"There will be a day when most semiconductor companies focus on design while outsourcing manufacturing to specialist foundries," Chang predicted. The tech world thought he was crazy. This was the era of vertical integration—Intel, Motorola, and National Semiconductor all designed and manufactured their own chips. Why would anyone trust their crown jewels to an outside manufacturer?

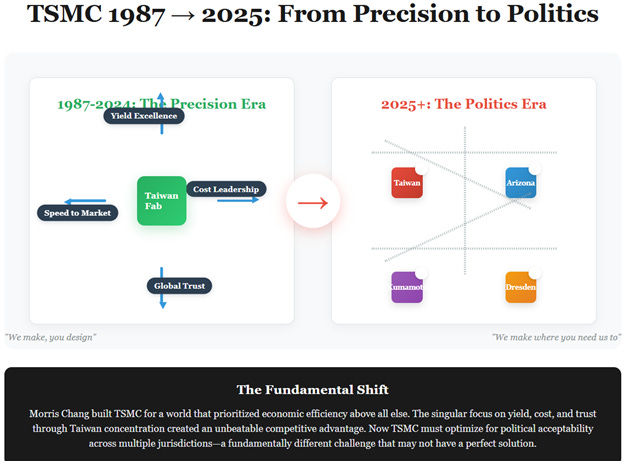

Chang's answer was elegantly simple: "We make, you design." TSMC would be the Switzerland of semiconductors—neutral, trusted, and focused solely on manufacturing excellence. The company would work equally hard for every customer, regardless of size or competitive relationships. This philosophical inversion of the industry standard seemed like a long shot in 1987.

The tech world thought horizontally; TSMC went vertical by staying horizontal.

Nearly four decades later, Chang's vision appears thoroughly vindicated. TSMC controls approximately 90% of the world's most advanced chip manufacturing capacity, producing processors for Apple's iPhones, graphics chips for Nvidia's AI systems, and semiconductors for virtually every major technology company on earth. The pure-play foundry model didn't just succeed—it became the dominant architecture of the global semiconductor industry.

But beneath the surface of TSMC's impressive financial performance lies a company undergoing the most structurally margin-dilutive transformation in its history. The very principles that made TSMC successful—concentration, neutrality, and singular focus on efficiency—are being challenged by forces Chang likely never imagined when he founded the company.

The Taiwan Advantage: Physics, Talent, Trust

TSMC's rise coincided perfectly with the golden age of globalization. From 2000 to 2018, the company created what might be called the Taiwan advantage—a unique combination of physics, talent, and trust that proved nearly impossible for competitors to replicate.

Everything was centralized: R&D, production, and engineering know-how concentrated in Taiwan's Hsinchu Science Park. This wasn't just a cluster—it was the crucible of leading-edge semiconductor development. Engineers could walk between research labs and production floors. Process improvements discovered in one facility instantly propagated across others. The concentration of talent and knowledge created feedback loops that accelerated innovation cycles far beyond what dispersed operations could achieve.

The physics were compelling. Co-located R&D and manufacturing meant that theoretical advances could be tested and refined in real-time. When a process engineer discovered a yield improvement technique at 2 AM, it could be implemented across multiple production lines by morning. This operational coherence became TSMC's secret weapon—the ability to move from concept to high-volume manufacturing faster than anyone else in the industry.

Culturally, Taiwan's position enhanced this advantage. The island's unique geopolitical status made TSMC genuinely neutral. Chinese companies trusted TSMC not to favor American customers. American companies trusted TSMC not to transfer technology to Chinese competitors. This neutrality was credible because it was structural—Taiwan had every incentive to maintain equal relationships with all major economic powers.

Efficiency and time-to-yield accelerated by cultural proximity and engineering density. Taiwan's pool of semiconductor talent was deep and specialized. Universities, government research institutes, and private companies created an ecosystem where knowledge flowed freely. Suppliers clustered nearby, creating efficiencies impossible to replicate elsewhere.

The result was a virtuous cycle that strengthened with each iteration: customers brought designs and capital, which funded massive R&D investments, which created technological advantages that attracted more customers, which generated more capital for even larger R&D investments. By 2018, TSMC had become the invisible center of the global technology stack, trusted by all and beholden to none.

Taiwan's geopolitically neutral positioning made TSMC the Switzerland of semiconductors—until the world stopped believing in Swiss neutrality.

Globalism Breaks Down

The first cracks in the foundation appeared around 2015, when China launched its "Made in China 2025" industrial plan with semiconductor self-sufficiency as a central goal. Initially dismissed as another ambitious government initiative, the plan represented something more fundamental: the beginning of the end for the post-Cold War consensus on technology cooperation.

By 2018, semiconductor technology had become a national security priority for the United States. The Trump administration began implementing increasingly aggressive restrictions on China's access to advanced chip technology. What started as targeted sanctions against specific companies like Huawei evolved into broader restrictions on entire technological categories. Export controls, once used sparingly for the most sensitive military technologies, became routine tools of economic competition.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these trends dramatically. When severe chip shortages brought automobile production lines to a halt across multiple continents, political leaders worldwide suddenly found themselves explaining to confused citizens why cars couldn't be manufactured due to semiconductor supply chain disruptions. The phrase "chip shortage" entered the popular lexicon alongside "supply chain" and "inflation."

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 delivered the final blow to globalization orthodoxy. If Vladimir Putin could weaponize energy supplies against Europe, what prevented Xi Jinping from weaponizing semiconductor supplies against the United States? Taiwan's precarious geopolitical position—the island that produces most of the world's advanced chips while living under constant threat of Chinese invasion—became impossible to ignore.

"Semiconductor sovereignty" became industrial policy across major economies. The United States passed the CHIPS Act, committing over $50 billion to domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The European Union launched its own chip strategy, targeting 20% of global production by 2030. China doubled down on domestic capabilities through companies like SMIC despite U.S. restrictions.

The world no longer wanted optimal—it wanted redundant.

March 2025: The Strategic Surrender

Throughout this period, TSMC maintained its traditional stance. When urged to build more capacity outside Taiwan, the company initially resisted, eventually making modest commitments to facilities in Arizona, Japan, and Germany while keeping the vast majority of advanced production concentrated in Taiwan.

That position became untenable in March 2025.

TSMC's announcement of a $100 billion expansion of its Arizona operations, bringing total U.S. investment to $165 billion, represented far more than another overseas facility commitment. The scope was breathtaking: three additional wafer manufacturing fabs, two advanced packaging facilities, and a major R&D center employing approximately 1,000 engineers. Most significantly, TSMC committed that "around 30% of our 2-nanometer and more advanced capacity will be located in Arizona."

This wasn't expansion—it was strategic surrender. For the first time in its history, TSMC would locate a substantial portion of its most advanced manufacturing outside Taiwan, abandoning the concentration strategy that had created its competitive advantage.

The financial mathematics revealed the transformation's magnitude. TSMC's management acknowledged that construction costs in Arizona are 4-5 times higher than Taiwan. The company forecasts gross margin dilution from overseas fabs will "start from 2% to 3% every year in the early stages and widen to 3% to 4% in the latter stages" over the next five years. Yet somehow, TSMC maintains it can preserve long-term gross margins of "53% and higher."

"Geographic flexibility" became the corporate euphemism for politics. TSMC's earnings calls started sounding like diplomatic briefings, with careful language about "value propositions" and "customer needs" masking the underlying reality: the company was being forced to sacrifice its core advantages for political compliance.

When asked about pricing strategy for overseas fabs, CFO Wendell Huang noted that "geographic manufacturing flexibility is an important part of our value proposition to the customers." This diplomatic language acknowledged a fundamental shift: customers were willing to pay premiums for geographically diversified production, but it also revealed that TSMC could no longer compete purely on manufacturing excellence.

What the Market Gets Wrong

Most investors still see TSMC as a high-margin monopoly with an unshakable technology lead, powered by AI tailwinds that justify current valuations. This view assumes that physics, politics, and geography are separable concerns. They're not anymore.

The consensus narrative treats TSMC's geographic expansion as a temporary margin headwind that preserves long-term value by reducing geopolitical risk. Analysts universally frame it as: "Best-in-class foundry with pricing power, executing necessary but costly diversification."

Current valuations reflect this optimism. A forward P/E of 18x assumes 20%+ earnings growth continues seamlessly through the transformation. The PEG ratio of 0.7 suggests the market sees growth at a discount despite transformation costs. Price targets averaging NT$1,240 imply successful execution of the $165 billion expansion with minimal return dilution.

But this consensus view misses three critical points:

· The "Moat Preservation" Fallacy: The market treats geographic expansion as preserving TSMC's moat by reducing geopolitical risk. In reality, the moat was created by concentration. Dispersing production across locations with 4-5x higher costs permanently weakens the competitive advantage that generated excess returns. TSMC's efficiency came from operational coherence—everything in one place, optimized for maximum throughput and minimum waste. Geographic fragmentation reverses this advantage.

· Customer Pricing Power Assumptions: Analysts assume customers will pay 20-30% premiums for "geographic flexibility" indefinitely. This is a temporary phenomenon. As Intel's 18A process and Samsung's 2nm technology mature with government subsidies, customer leverage will increase. The "national security premium" will compress rapidly as alternatives emerge.

· Technology Leadership Sustainability: The consensus assumes R&D leadership ensures continued premium pricing regardless of geography. But fragmenting research and development across multiple locations—Arizona's R&D center, Taiwan's labs, Japan's facilities—will slow innovation cycles. TSMC's speed advantage came from co-located research and manufacturing. Engineers could implement process improvements in real-time, test new techniques immediately, and iterate rapidly. This tacit coordination becomes much harder across time zones and regulatory jurisdictions.

The market is extrapolating TSMC's 2020-2024 performance—high growth, expanding margins, pricing power—into a fundamentally different operational structure. The AI boom has created euphoria that obscures the underlying business model degradation. Investors are rationalizing obviously value-destructive capital allocation because it appears "strategically necessary." This is classic narrative-driven investing where story trumps mathematics.

Most critically, current earnings power reflects peak efficiency from Taiwan concentration. The profit and loss statement won't show overseas dilution until 2026-2027, creating a 2-3 year lag between the strategic decision and visible financial impact. By the time the margin compression appears in reported results, it will be too late to adjust positions at favorable prices.

Strategic Dilemma: A Company Becoming Less Like Itself

TSMC now faces a profound paradox: to remain indispensable, it must become less TSMC-like. The company's original advantages are structurally incompatible with its new geopolitical reality.

· Concentration vs. Diversification: TSMC's efficiency advantage has always stemmed from concentrated manufacturing in Taiwan's semiconductor ecosystem. Everything optimized for maximum throughput: shared R&D costs, instant knowledge transfer, rapid problem-solving through physical proximity. By distributing production across multiple countries, the company inevitably sacrifices this operational coherence. The question isn't whether diversification reduces efficiency—it's whether the strategic benefits outweigh the operational costs.

· Neutrality vs. Alignment: TSMC built its reputation on serving all customers equally, regardless of their competitive relationships or national origins. This neutrality was credible because it was structural—Taiwan had incentives to maintain relationships with all major powers. But operating across multiple jurisdictions inevitably means navigating different governmental priorities. The second a wafer is manufactured in Arizona, it becomes subject to U.S. export control policies, potentially limiting which customers can access that capacity. Can TSMC remain genuinely apolitical when its facilities are distributed across competing political systems?

· Engineering Singularity vs. Geopolitical Fragmentation: TSMC has always maintained unified technology development—one roadmap, one set of processes, one standard of excellence. This singularity enabled the company to move faster than competitors who struggled with internal coordination across divisions. As overseas facilities mature and potentially specialize based on regional customer demands or regulatory requirements, maintaining this technological unity becomes increasingly challenging.

· Margin Leadership vs. Redundancy Costs: TSMC's financial success stemmed from optimizing for economic efficiency above all other considerations. Every decision prioritized margin improvement and capital efficiency. Now the company must optimize for political acceptability and supply chain resilience, objectives that often conflict with pure economic optimization. The costs of redundancy—duplicate R&D, multiple regulatory compliance systems, fragmented talent pools—represent permanent drags on returns.

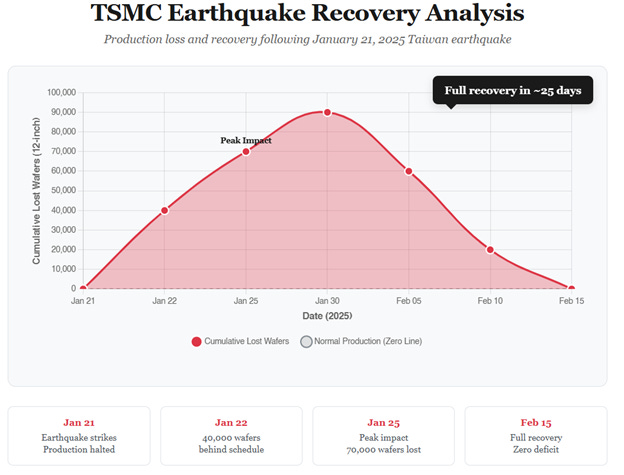

The January 21, 2025 earthquake that struck Taiwan provides a telling example of these tensions. TSMC reported approximately NT$5.3 billion in earthquake-related losses for Q1, with the event impacting gross margin by about 60 basis points. Yet Chairman and CEO C.C. Wei also praised employees who "worked tirelessly" over the Lunar New Year holiday to "recover much of the lost production."

This resilience demonstrates the advantages of concentrated operations—dedicated teams, redundant systems within facilities, rapid response capabilities. But it also highlights the vulnerability that customers and governments are increasingly unwilling to accept, regardless of the efficiency advantages concentration provides.

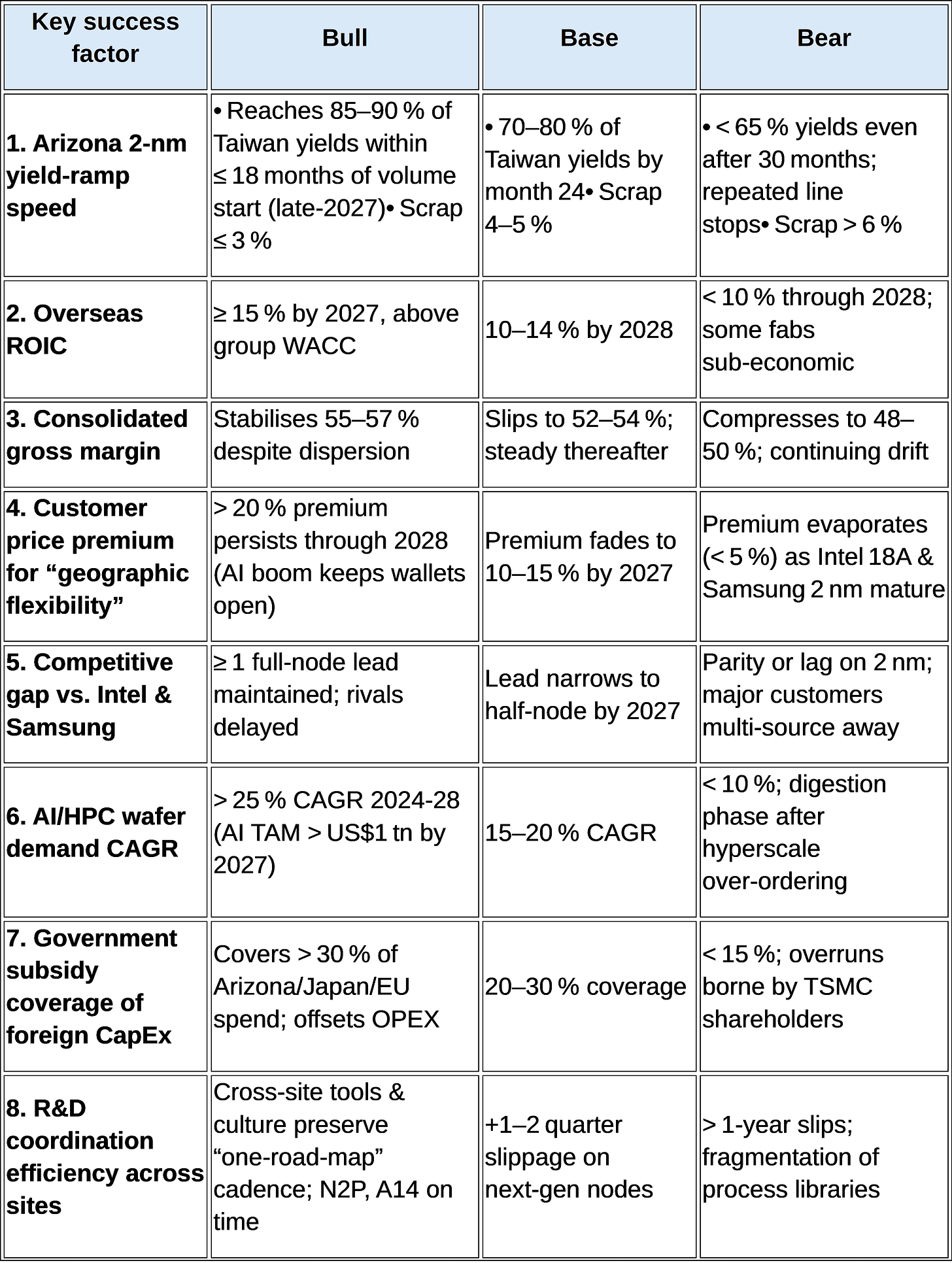

Three-Scenario Framework: What the Next 3 Years Could Look Like

The interaction between TSMC's execution capabilities, competitive dynamics, and geopolitical developments will determine which of three scenarios emerges by 2028:

Bull Case: Arizona Achieves Near-Taiwan Yields

Price Range: NT$1,600-1,900

In this scenario, TSMC demonstrates that technological excellence can overcome geographic disadvantages. Arizona facilities achieve 85-90% of Taiwan yields within 18 months of volume production. Government subsidies prove more generous than expected, offsetting much of the cost differential. AI infrastructure spending accelerates to over $1 trillion annually by 2027, creating pricing power that overwhelms cost structure concerns.

Key Assumptions:

Arizona operations reach 15%+ ROIC by 2027

Margins stabilize at 55-57% despite overseas expansion

AI demand sustains 25%+ CAGR through 2028

Geopolitical "premium" pricing endures as customers value supply chain diversification

P/E multiple expands to 22-25x as TSMC proves it can excel globally

Catalysts: Successful N2 ramp in Arizona, major customer commitments for advanced packaging, technology leadership gap vs. Intel/Samsung widens further.

Base Case: Execution Remains Solid, But Global Costs Weigh

Price Range: NT$1,200-1,400

TSMC executes competently but not flawlessly. Arizona yields reach 70-80% of Taiwan levels—good enough for production but highlighting the challenges of replicating world-class operations. AI demand remains strong but normalizes to 15-20% growth as infrastructure buildout matures. Competitive pressure from subsidized Intel and Samsung increases gradually.

Key Assumptions:

Blended ROIC declines to 18-22% as overseas mix increases

Margins stabilize at 52-54% through operational improvements and selective pricing

EPS growth moderates to 12-15% annually

Customer pricing power for geographic flexibility diminishes but doesn't disappear

P/E multiple settles at 16-18x reflecting new competitive dynamics

Catalysts: Steady quarterly execution, moderate competitive gains by Intel/Samsung, stable geopolitical environment.

Bear Case: Cost Overruns Abroad, Yield Degradation, Slowing AI

Price Range: NT$850-1,050

Arizona operations struggle with yield and cost issues. The complexity of replicating Taiwan's ecosystem proves greater than anticipated. AI infrastructure spending slows as deployment efficiency improves and economic pressures mount. U.S.-China tensions escalate, fragmenting the global semiconductor market and forcing TSMC to choose sides.

Key Assumptions:

Arizona ROIC remains below 10% through 2028

Margins fall to 48-50% as overseas dilution accelerates

EPS growth flattens or turns negative

Competitive pressure intensifies as Intel and Samsung gain government support

P/E multiple compresses to 12-14x reflecting commodity-like competition

Catalysts: Arizona production problems, major customer defections to competitors, geopolitical escalation forcing capacity restrictions.

The Trap of Being Too Important to Fail

TSMC has become too strategically important to remain truly independent. The company now operates at the intersection of national security policy, industrial strategy, and technological competition between superpowers. This creates a unique set of constraints that didn't exist during the company's rise.

Customers no longer view TSMC purely as a vendor—they see it as critical infrastructure that must be protected and diversified. Apple, Nvidia, AMD, and Qualcomm are all pushing for geographic distribution of production, not because it's economically optimal, but because concentration risk has become unacceptable. These same customers are simultaneously the company's largest revenue sources and its most demanding stakeholders regarding supply chain resilience.

Governments view TSMC as a strategic asset that transcends normal business considerations. The U.S. government provides subsidies and regulatory support but expects political alignment in return. The Taiwan government sees TSMC as both an economic engine and a geopolitical shield—too valuable for China to risk destroying through invasion. China views TSMC as a strategic vulnerability that must be either controlled or replaced through domestic alternatives.

This web of dependencies creates what might be called "strategic capture"—TSMC's business decisions are increasingly constrained by political considerations rather than pure economic optimization. The company can no longer simply pursue the most efficient manufacturing strategy; it must balance efficiency against political acceptability across multiple jurisdictions.

The business is becoming geopolitically managed, even if technically independent. Management spends increasing time on diplomatic engagement rather than operational excellence. Capital allocation decisions must consider political ramifications alongside financial returns. Strategic planning requires scenario analysis across multiple geopolitical outcomes, not just market and technology trends.

This represents a fundamental change in the nature of the business. TSMC was built to optimize for manufacturing excellence in a globalized world. It must now optimize for political sustainability in a fragmenting world. These objectives often conflict, creating permanent tension in strategic decision-making.

Conclusion: Precision Built, Now Politically Pulled

Morris Chang built TSMC for a world that prioritized economic efficiency above all other considerations. The company's original blueprint was calibrated for trust, neutrality, and optimization—principles that thrived during the post-Cold War expansion of global trade.

That world is gone. The next version of TSMC must navigate power, alliances, and redundancy. Political considerations now override pure economics in ways that Chang likely never anticipated when he founded the company. The elegant simplicity of "we make, you design" has given way to complex calculations involving export controls, government subsidies, and geopolitical alignment.

TSMC's transformation reflects a broader shift in how critical technologies will be developed and deployed in an increasingly fragmented world. The pursuit of efficiency through globalization has yielded to the pursuit of resilience through regionalization. Supply chains once optimized for cost and speed must now account for political risk and strategic autonomy.

The question is no longer "Can TSMC execute?" The company has proven its operational excellence repeatedly across multiple technology generations. The real question is: Can TSMC reinvent itself without breaking its internal physics?

The answer will determine not just the company's future, but the broader architecture of global technology development for decades to come. Chang's original vision built the most successful semiconductor manufacturing company in history. Whether C.C. Wei's vision of distributed, politically acceptable, strategically aligned manufacturing can maintain TSMC's excellence while satisfying competing political demands remains to be seen.

What's certain is that the company emerging from this transformation will be fundamentally different from the one that entered it. Investors betting on TSMC today aren't just betting on semiconductor demand or AI growth—they're betting on the company's ability to preserve its essential character while adapting to a world that no longer values pure efficiency above all else.

For nearly four decades, TSMC thrived by being precisely what the market needed. Now it must learn to be precisely what politics will allow. The precision remains, but the pressure has changed everything.

#TSMC #TooImportantToFail #CHIPSAct #AIInvesting #SupplyChainSecurity #StrategicCapture SOXX 0.00%↑ SMH 0.00%↑ TSM 0.00%↑ $2330:TWSE